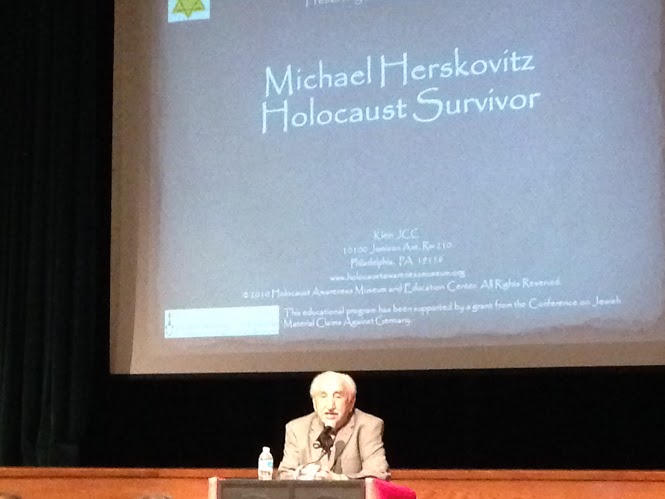

Holocaust Survivor Speaks at Haverford

For what could be the last time in history, Haverford students listened to a firsthand account of a Holocaust survivor. 86 year-old Michael Herskovitz spoke with a thick accent and an aged voice, but the poignancy that his words carried was told with absolute clarity.

“I never knew I was different than the other kids, ‘till one day a German uniform walked through village,” Mr. Herskovitz spoke briefly of his life in the small Czechoslovakian village where he grew up, and how the entrance of the Germans began to end life as he knew it.

First, the Jewish children were not allowed to attend school, then the synagogue was closed, and soon they were not even allowed outside without the infamous yellow star.

And soon, even these rigid regulations were not enough for the Germans, and the Herskovitz family was shipped out in a dark train car, empty except for other Jews and a bucket in which to relieve themselves. The closer the train traveled to it’s destination, the more Jews were loaded into the trains, until the doors were opened, the Germans looted whatever valuables were left on the deported people, and hundreds of soldiers with dogs forced them into Auschwitz.

Men were separated from their families, children from their parents, never to see them again. Michael managed to stay with his father while they were forced to strip down, hand in their clothes, and all hair was shaved from their bodies.

But trading the striped prison garb with another inmate, Mr. Herskovitz turned back around, and was unable to find his father. He never saw him again.

Mr. Herskovitz then spoke of the barracks- being lead in past a sign in german that read “Work Will Set you Free”. There were hundreds of bunks, stacked three tall, each holding around 18 people.

“Every morning was selection- inmates were evaluated, and if the inspector didn’t like how you looked, if you had been crying or were too thin…you were taken away.”

Mr. Herskovitz worked scrubbing the floors of the barracks, managing to get through every evaluation. But if any of the Jews were working too slow, or the Germans found some fault in their work, there was no hesitation to shoot the inmates.

As Mr. Herskovitz spoke, the quiet of the room became more oppressive, the tension hanging in the air and pulling any cheer from the auditorium.

“There was no time- we didn’t know what day it was. Only light and dark…You never knew if you were going to be picked or going to be shot.”

Mr. Herskovitz soon spoke of one of the darkest, most infamous faces of the Holocaust era- the gas chambers and crematoria.

“Grandpas and Grandmas were told they would be fed and taken back to families- they were lead into a building to get showers, but there were no showers. Poisonous gas came from the ceiling. Then young men in civilian clothes came in and stripped the bodies (of clothes and hair), and then burned the bodies in the crematorium…The human ashes lingered too long…”

Mr. Herskovitz paused many times throughout the assembly, fist at the mention of “Auschwitz”, and then at this point of his recollection, speaking of death by poison and death by fire.

After more details and accounts of his survival in Auschwitz, Mr. Herskovitz told of his incarceration at a second camp, where the mud and hunger drove people back to instinctive survival.

“If you did not put your bread in your mouth, people would take it. Not because they were nasty, but because they were hungry,” Herskovitz mentioned the animalistic need for survival- even taking the clothes of someone asleep or dead in the mud, if they looked cleaner or warmer than your own rags. And even without teeth or gums, they continued to try and eat, surviving for fear of dying in such a hellish place.

Then one day the guards disappeared. The fence surrounding the imprisonment- one climbed only with a deathwish- was now crossed. Michael Herskovitz- starving, practically toeing the line with death- escaped with a few others. Crawling through gutters and eating filthy, uncooked meat, Mr. Herskovitz remembered waking up in a hospital with typhus, alone and without knowing if any of his family was still alive. Eventually, his uncle found him, and he discovered that one sister and one brother had survived.

And this is where Mr. Herskovitz’s story took a remarkable turn- his life continued. He did not let his Holocaust experience define him, but he got back up, and created a new life for himself. He grew into a young man, got married, and worked in a mechanic’s garage and ended up owning a gas station. He was not destroyed by what Nazi Germany tried to achieve, he did not break. Mr. Herskovitz is a survivor, and Haverford students had the honor and privilege to hear of his victory.