Cultural mindsets tend to follow politics, and politics tend to follow cultural mindsets. The overwhelming sweep of Republicans in the recent 2024 election, taking a majority in the House of Representatives, Senate, and the White House under newly inaugurated President Donald Trump, could be seen as one product of the return to religion, specifically the Christian faith. Mass attendance and church membership have increased, as noted by religious leaders, after significant declines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Republican leaders have often relied on the Christian bloc to secure votes, using faith and religiosity as ways to connect with voters. But the faith has seen a push to return to a place least expected: public schools.

The Supreme Court has been very clear about the role of faith in public schools — they do not go hand-in-hand. Public schools are considered purely secular spaces. However, that hasn’t stopped a recent wave of lawmakers and zealots from trying. In Louisiana, a law was recently passed requiring the Ten Commandments to be displayed in all public school classrooms. In Texas, a new curriculum with Bible-infused lessons for elementary schoolers was implemented amid controversy. And in Oklahoma, 500 Bibles were purchased for students enrolled in AP U.S. Government.

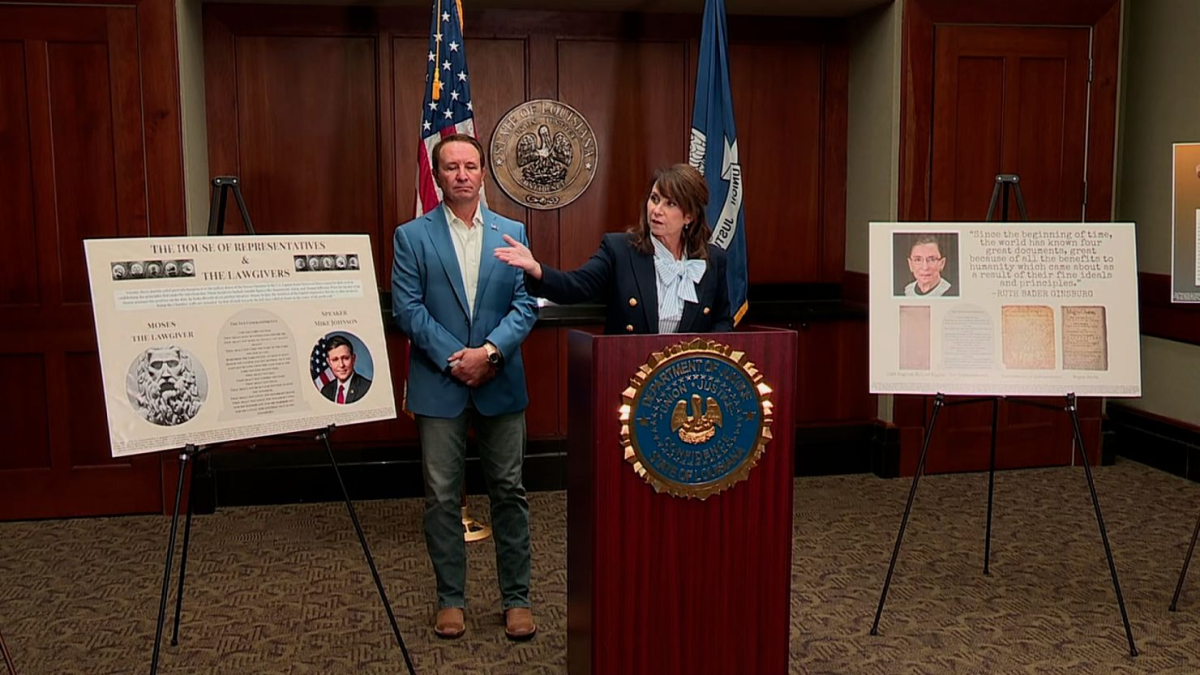

The motivations behind these decisions vary depending on who’s making them, but they all share the goal of reintroducing “religious freedom” into the classroom. When signing the new bill on the Commandments, Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry stated “If you want to respect the rule of law, you’ve got to start from the original lawgiver, which was Moses.” Ryan Walters, Oklahoma’s state superintendent on public education, called the Bible an “indispensable historical and cultural touchstone” in American history and a “core foundational document.” Walters has also created a new bureau within the state’s education department called the “Office of Religious Liberty and Patriotism.” Its mission statement says that schools are not “religion-free zones” and that students and teachers should be able to exercise their faith freely and openly.

Oftentimes, response to critics on the subject of religious favoritism is met with the spirit of honor for American legacy and antiquity. Proponents of these initiatives may point out the heavy hand that the Christian faith holds in founding documents such as the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution. However, these initiatives violate the principle of separation of church and state fostered by political think tanks and leaders of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Thomas Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration of Independence, also drafted Virginia’s Statute for Religious Freedom for the Virginia General Assembly in 1786. He was inspired by the Anglican Church’s domineering role as a prosecutor of religious minorities in the state prior to the American Revolutionary War, and he believed church and state should be separate. The statute’s core principle was that citizens of the state are allowed to practice any faith or creed and should not suffer physically, financially, or professionally. Jefferson’s document would go on to influence the Bill of Rights Establishment and Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Similarly, Congress is unable to enact a state religion sponsored and promoted by the government.

Religious leaders of the late 18th century also were critical of entanglement between the church and state. New England-born Baptist leader John Leland was crucial in his support of Thomas Jefferson and disdain for Baptist prosecution in Virginia. In A Chronicle of His Time in Virginia, Leland writes, “The notion of a Christian commonwealth should be exploded forever. … Government should protect every man in thinking and speaking freely, and see that one does not abuse another.” His sentiments were shared by other Baptist leaders of Buckingham County, VA, who stated that government disinterest in religion “is the only way to convince the gazing world, that Disciples do not follow Christ for Loaves, and that Preachers do not preach for Benefices.”

The issue of religion in public school is hardly new. In the 1971 court case Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the Supreme Court ruled that coaches could not lead their players in prayer before high school sports events, regardless if participation was voluntary. As a result, the Court developed “The Lemon Test,” a three-pronged approach to determine if the Establishment Clause was violated. For a government action to have not violated the First Amendment it must 1) have a secular, non-religious purpose, 2) not advance or inhibit a religion, and 3) not promote any extreme entanglement with religion on the government’s part. The test has seen tweaks and changes over the years, but was used in the 1980 case Stone v. Graham, when Kentucky tried to enact a similar law as Louisiana, and by Oklahoma’s state court, when the state tried to fund an unambiguously Catholic charter school. Over the recent years, however, the test has fallen out of favor as more conservative judges look towards the early reaches of American history and law to determine verdicts on modern issues.

However, all this is not to say that students shouldn’t practice their faith. Religion can provide students with a sense of community, belonging, and charity. The Christian ministry YoungLife, which has a chapter in Haverford, seeks to embolden faith in students through service acts, Bible study, and retreats. They aim to “introduce adolescents to Jesus Christ and help them grow in their faith.” “[YoungLife]’s a great way to connect with other people…who are Christian,” said junior Mia Dolan. “It’s a very positive environment where you get to explore what you think of everything.” Senior Abbey Gandy agrees, saying “[YoungLife] helps me get closer to God in my faith, and I got closer with a lot of people. It helped me have a community when I didn’t really have one.” These services are private, and not sponsored by state education systems or taxpayer dollars that are allocated to schools.

The courts, lawmakers, and religious zealots are increasingly looking to America’s tradition, antiquity, and legacy to justify the inclusion of religion in public schools. However, the Bible isn’t a core document of American history in the way it is being used. The Bible isn’t the same as the Declaration of Indepence; the book has been used to manipulate the narratives of Native Americans, to spur conquest of previously owned Native lands, to justify war, and to justify discrimination based on race, sex, sexual orientation, and other religions. While the Bible has certainly been a source of inspiration for prominent politicians, civil rights leaders, activists, Samaritans, and charitable organizations, it is not a creed of the United States. Its influence, rather than its teachings, deserves a place in history curricula. However, when “teaching the Bible” is written into curricula, state governments engage in religious favoritism, not religious freedom. It causes children who aren’t Christian to feel like outsiders in their schools.

Proponents of these plans argue that the laurels of America rest on the laurels of Christianity and that their initiatives are champions of the First Amendment. This just isn’t the case, and it violates the beliefs of early American religious leaders and governing officials.

Interestingly, the states where these programs have been approved often fall behind in education rankings for all subjects. A data analysis from WalletHub that examined 18 metrics of education found Texas to be ranked 41st, Kentucky 43rd, Oklahoma 46th, and Louisiana 48th in public education for the United States in 2024. Adding these religious practices to already suffering education systems wastes taxpayer dollars that could support teachers’ aides, school programs, and supplements to enrich student development. To skeptics, the answer is apparent: lawmakers are embedding their religious preferences into public education as “religious freedom.” If the courts continue to shy away from upholding the long established precedent of “separation of church and state” valued by the framers of the nation, they do American students in public education an injustice to the virtues and legacy of the nation.